“How much does your intended major matter for college admissions? Does listing Latin or Classics, for example, help if you have the appropriate classwork and activities to back it up?”

- Parent of a twelfth grader in Westchester County, New York

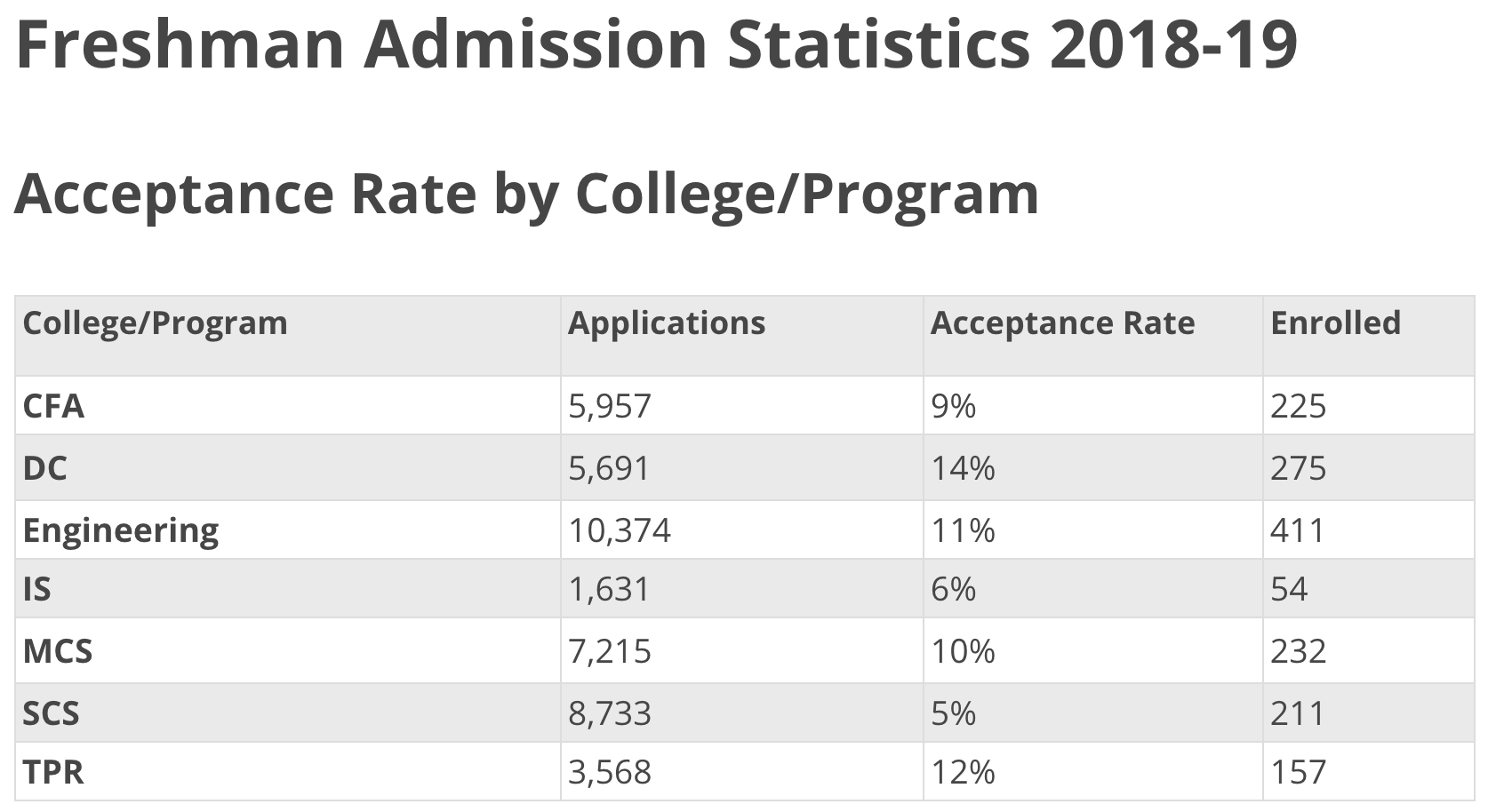

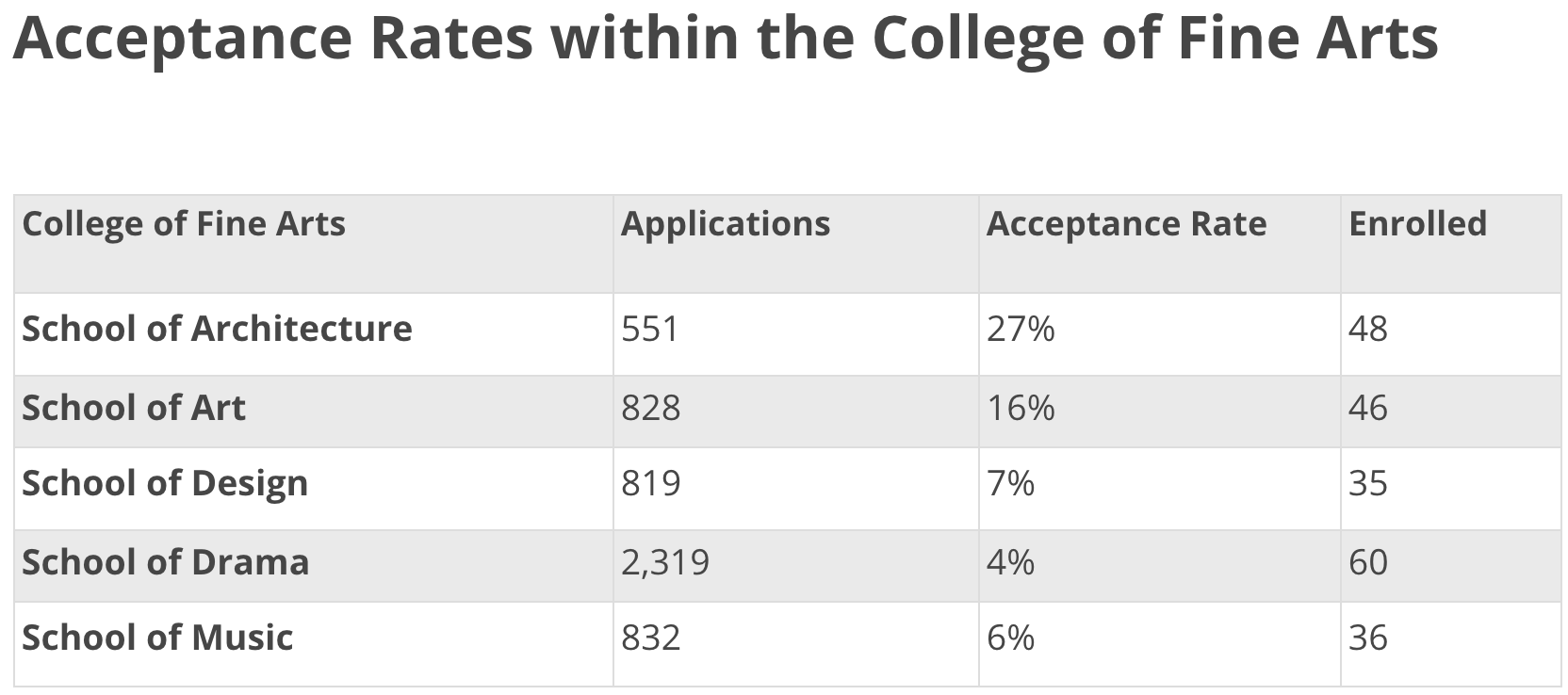

Your intended major does matter and can influence your chances of admission. Just as an example, let’s take a look at Carnegie Mellon University’s 2018 undergraduate admission statistics by school. The acceptance rate ranges from as low as 4% in the School of Drama to 27% in the School of Architecture. Although this guide doesn’t include a breakdown by specific major, the breakdown by individual schools tells you that in order to create a balanced freshman class, admissions committees take into account your selected major during application review.At Carnegie Mellon, a top computer science institution, the School of Computer Science (SCS) boasts an acceptance rate of 5%, nearly three times more selective than the Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences at a 14% acceptance rate.

Private college consultants oftentimes use this reality to help their clients gain admission into top colleges by “packaging” them into a suitable or strong candidate for a less impacted or less popular major (Scandinavian Studies, Latin/Classics, Performance Studies, etc.) and insisting they eventually switch into their truly desired major (typically something impacted like economics, biology, engineering, communications, psychology, etc.) after getting in.Take this account from a father who revealed how the college consultant he hired used the strategy of repackaging her daughter into a rarer breed:

“So here’s what this woman does. She creates a new profile for our daughter–a whole new persona. No more talk about loving math and science and wanting to be a doctor. She doesn’t care if the kid’s already a doctor. Brown and Yale are overloaded with them already. She notices our daughter has take some Latin, so she tells her to downplay the math and science and announce her intention of majoring in classics. That should impress them!’”

Anne C. Roark describing a father she encountered, I’m Going to College–Not You! p. 53

It didn’t work out. She was rejected by the big guns and the most of the “medium-guns.” Anne later heard through the grapevine that the daughter eventually grew fond of where she ended up, but her father was “still recovering.”

When I worked as a private college consultant, my more experienced peers would suggest that I use this “repackaging” strategy with my clients. My clients comprised of mainly high-achieving students from tiger families with a tight grip on their children’s future — or to put it nicely, tiger families highly invested in their children’s future. However, a few things stopped me from recommending this to many students.

Firstly, I was concerned about how well they’d be able to prove interest in their “consultant-chosen” major. Most high schoolers struggle to even articulate why they want to study a major that truly interests them, let alone one like classics that they selected due to unpopularity. I’ve read, revised, and edited countless “Why My Major?” student essays.