Exclusive Insider Interview: Parents of two Stanford students and high school valedictorians

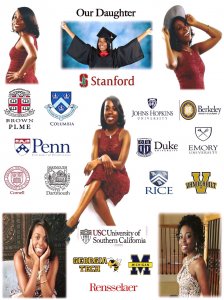

UPenn, Dartmouth, Duke (with scholarship), Berkeley, Emory (with scholarship), Johns Hopkins, Georgia Tech (with scholarship), Johns Hopkins, USC, UMich (with scholarship), Rensselaer, Rice, and Stanford, where she matriculated. Two years later, her younger brother, Anthony Mays II, graduated in 2019 with a 4.93 GPA, boasting acceptances to Harvard, Penn Wharton, MIT, Columbia, Cornell, Brown, Dartmouth, USC, UCLA, Georgia Tech (with scholarship), Rensselaer, UGA (with scholarship) and Stanford, where he also chose to go.

UPenn, Dartmouth, Duke (with scholarship), Berkeley, Emory (with scholarship), Johns Hopkins, Georgia Tech (with scholarship), Johns Hopkins, USC, UMich (with scholarship), Rensselaer, Rice, and Stanford, where she matriculated. Two years later, her younger brother, Anthony Mays II, graduated in 2019 with a 4.93 GPA, boasting acceptances to Harvard, Penn Wharton, MIT, Columbia, Cornell, Brown, Dartmouth, USC, UCLA, Georgia Tech (with scholarship), Rensselaer, UGA (with scholarship) and Stanford, where he also chose to go.

On top of all that, Chyna just finished an internship at NASA and serves as VP of Stanford’s Society of Women Engineers.

Demeka’s an educational consultant who started her career as a classroom teacher. Throughout her career, she’s served as a district director of curriculum instruction, building leader, district instructional leader, superintendent- and- governors’ council member, Dept. of Ed. program specialist and college writing instructor.

Her husband, Anthony, is an engineer and former Army officer. When the kids needed to learn math, science, and business management, they turned to dad who helped develop them into the STEM-focused individuals they are today.

Chyna and Anthony were precocious kids, thanks to mom who took teaching into her own hands.

“And as most parents do with early learners, I taught them how to read, write, how to do math. They were reading at age three, both of them, and writing. We started with simple sentences at age three; they were writing paragraphs by kindergarten,” Demeka said.

Demeka and Anthony wanted their kids to be ahead of the curve.

“We always tried to teach them the concepts and skills prior to the next grade in which they were being promoted. So they were never really being introduced by the teacher to the learning. It was more of an extension of what we were already doing at home. It was very important to me that they were always one or two grade levels ahead. And because I’m a public school educator, I believe in public school education, and so my kids were going to go to public school,” Demeka continued.

While many American parents think that public schools tend to fall short of private schools, Demeka instead tried to dispel that myth.

“I was the Miami-Dade County Teacher of the Year…so it would not be a good look for me to put my kids in private school. So my kids were in public school, and I wanted to show that public school can work when parents partner with educators in their children’s learning.”

“Basically, I was their humanities coach, supporting them with Social Studies, English Language Arts, and writing. My husband was their math and science coach,” she responded.

Aside from coaching their kids on academic subjects, Demeka and Anthony made sure to sharpen their kids’ study skills — early. While most kindergarteners were learning how to operate the iPad and play in the park, Anthony and Chyna were getting the hang of self-analysis and self-assessment.

Demeka explained, “They’ve been analyzing and using data and conducting self-assessments and reflections and goal setting since kindergarten. We would pull out the report cards, any test results that they would get and teach them how to read that data and to draw conclusions from their data and to reflect on, ‘What are my strengths? What are my areas for improvement?’ These behaviors served them well in the college admissions process.”

I couldn’t help wondering how the kids survived all the work at home: analyzing report cards, getting coached on math and English, and writing paragraphs by the age of 5.

But Demeka clarified how that all looked.

“The interesting thing is people think they didn’t have a normal childhood. Anybody who knows them will tell you that they had a normal childhood. As a matter of fact, my friends would say, ‘They were outside playing and don’t study as much as our kids. When do they have time to…?’

Driving to school?

“We constantly asked questions, we constantly had discussions, even in the car on the way to school. We would play games like reading the signs on buildings as we pass,” Demeka said.

At the grocery store?

“Going to the grocery store, having them to estimate how much the bill would be by the time we get to the register, to read ingredients. There were just so many opportunities to learn in real-world settings. There are so many opportunities for parents, who are not educators and who don’t know how to formally instruct, to teach their children by using routine activities.”

Eating dinner?

“Doing things over dinner, having discussions about their day, about whatever we watched on television, about the news,” she exemplified.

Getting ready for school or work in the morning?

“One of the things I’ll never forget–and this is interesting, because I did forget–in the morning, whenever we were getting ready for school, the news would be on. And so we would all get dressed together. And then they would point out things that they would see on the news and so would I, and we would talk about it. And then I would connect it back to something that they were learning in the classroom,” Demeka remembered.

Watching cartoons?

“As early as three, four, or five, they’re watching cartoons. I’m asking them the key characteristics of plot: the who, what, where, when, and why; who are the characters; asking them about motivation: why do you think that character did this or that?”

Going on family vacations?

“We took them to Italy, France, Spain, and they had their travel journals. We watched a lot of documentaries before even traveling over there. We read articles. They were learning about world literature and world history in the classroom, but they were able to connect the dots when we traveled overseas. And so they learned about the architecture in Rome. They learned about government, they learned about the culture and food and all of that…we took our kids on field trips, and it just enhanced their learning experience.”

Hardly the normal experience that I see kids having when traveling with family: being scolded by parents for not keeping up with the adults on a walking tour or bribed with an iPad to stay quiet during dinner at a fancy restaurant.

So how did all this fit into their college journey? Chyna and Anthony very well-supported by their parents who contributed significant personal time and effort into teaching them not only the what but also the how to. They were advanced.