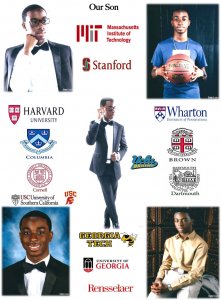

The Mays helped their kids get into schools like Stanford, Harvard, MIT, UPenn, Brown, Dartmouth, Columbia, and Berkeley — all without hiring outside consultants. How did they keep their kids healthy and motivated? How did their guidance differ between their son and daughter, a NASA intern? How did they create a college list and advise on getting rec letters? What surprised them during the college app process? We continue our insider interview this week.

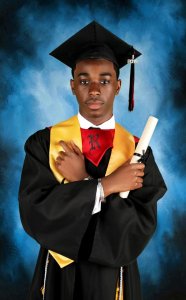

Exclusive Insider Interview: Parents of two Stanford students and high school valedictorians

Was Chyna okay and if so, what did her parents do to make sure she didn’t collapse under the weight of all her commitments, as many teenagers do?

Demeka and Anthony emphasized time management.

“From elementary school, we taught them about time management…That was a habit that they had to develop over time. We coached her early on about maintaining a calendar. When she was younger, it was a paper calendar, which evolved to a wall calendar. And then she also used, of course, Google calendar,” Demeka explained.

But time management and using calendars even as young kids wasn’t the only key. There was also an aspect of prioritizing.

“Some of the things we had to coach her on, because she had so many activities, was about prioritizing — which activities were more important than others — because sometimes there were conflicts…We would have to coach her on how to break it up into manageable chunks, so that everything wasn’t piling on her at one time.”

With Chyna’s various leadership roles, she practiced how not to overwhelm herself and spread the work among her team.

With Chyna’s various leadership roles, she practiced how not to overwhelm herself and spread the work among her team.

“Because she was a leader in almost all of the organizations in which she was involved, also learning how to delegate responsibilities to others, so that she had some teamwork going on. So if there was an event that she couldn’t make, she was responsible for helping to plan it and coordinate everything, but maybe somebody else had to facilitate it on that day.”

That skill, Demeka says, has helped her in college and at work (as a NASA intern, no less).

“That has been something that has been a plus for her because at Stanford, she’s now one of the vice presidents for the Society of Women Engineers. This summer she interned at NASA, and she was the only intern in her division, and they really delegated this major project to her and she had to go out and coordinate with these other divisions; she had to really come up with a project by herself and do presentations on the spot. So those soft and technical skills that she learned from her activities and through business management really helped her to manage her time.”

The Mays parents were careful to instill important skills like time management, prioritizing, and delegating early on in Chyna’s development. But this story isn’t only about Chyna. It’s also about her younger brother, Anthony, who is also a Stanford student.

“How did your guidance for your son Anthony differ?” I asked Demeka and Anthony, fully aware that what parenting methods work for one child may not work for the other. There’s always a mix of personalities at play.

Turns out, Chyna and Anthony (II) displayed different strengths, which their parents noticed.

Their dad Anthony (I), chimed in, “My daughter was more of a self-starter and go-getter than my son. Academically, his stats were probably slightly higher than my daughter’s and learning came more naturally for him.”

Anthony rarely backed down from a challenge, his parents expressed. He met almost every objective either he or his parents set.

“My daughter strived to get a 100 in everything that she did. If we told my son, ‘Hey, if you get a 90, then that’s good,’ then he would get a 90. Then if we said, ‘Okay, if you get 95, then that’d be good,’ and then he’d come and get a 95. And then it was like, ‘Well, why didn’t you get a 95 before?’ He was like, ‘Well, you didn’t ask me to.’ So we’re like, ‘Well, we want you to get 100.’ And so he’s like, ‘Okay, you want me to get 100, I’ll get 100.’ Basically, whatever objective we gave him, he would meet,” the kids’ father remembered.

Knowing their son’s strong capabilities in attaining his goals, the parents knew that clarifying objectives was going to be the key to guiding him through college apps.

“We just saw from that perspective that we had to give him more guidance as far as,

Hey, this is what we want you to do.’ My daughter has a little bit more initiative. In the application process, she was more of a self-starter. She pursued a lot of leadership opportunities and she would always stand out. With our son, he was a leader, but in his own perspective. He let other people lead, he interjected when it was asked, and he attributed to the team, but he wasn’t necessarily the focal point or the go-to person,” Anthony (I) said.

How did that look? Their son served as a 21st Century Leader, a Model Atlanta Regional Commission school representative, and captain of his community basketball team.

“With our daughter, she strived for a lot more in-school activities, and his was more out of schools. That was the main difference. Academically, they both excelled as far as classroom and test scores,” Anthony explained.

The siblings were competitive yet encouraging with each other. Motivation to succeed rarely emerged as a problem and the parents appreciated that. Time that would’ve been spent on motivating them was instead spent on helping them find their strengths, instill skills, and set the right objectives.

The parents were cautious to reiterate one thing: Chyna and Anthony were striving for their own personal goals, not a vague goal coming from their parents’ direction.

They were responsible for understanding the goals their kids themselves chose and then breaking them down into smaller, more digestible pieces, like the rungs of a ladder.

“Like other high achievers, they would get discouraged and feel like they were reaching their tipping points,” Anthony admitted. “And we wanted to assure them that this was their goal. We never said that Yale, Harvard, or Stanford were our goal for them. We wanted to let them know that this was their goal, and we tried to help them understand that in order to get to this particular goal, these were some of the things that they were going to have to do because there were thousands of people that they were going to be competing against.”

When it came time to compile a college list, Demeka and Anthony asked the kids to apply to a large variety of schools, since admission was never guaranteed.

The one non-negotiable aspect, though?

They were only allowed to apply to affordable schools.

What did that mean, exactly?

Demeka and Anthony spoke honestly about what the family could afford and asked their kids to consider the downsides of working hard to gain an acceptance to a school they couldn’t pay for.

They created their first college interest list in the eighth grade because that was going to inform the regional college tours that we would take throughout high school.

This simple practice helped Chyna and Anthony easily apply for competitive leadership programs, scholarships, and even obtain recommendation letters without writing a new resume each time.